How the U.S. Could Reduce Debt Without Breaking the Economy

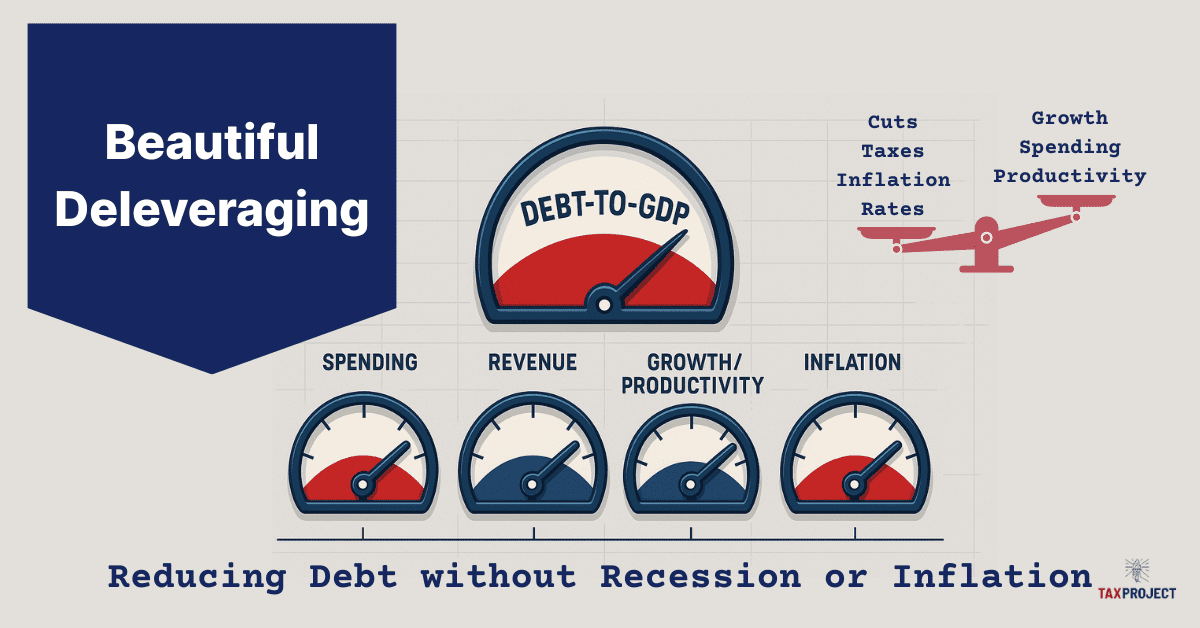

The U.S. National Debt just passed $38 trillion according to the US Treasury’s Debt to the Penny. [1][2] Not all debt is bad, but if it gets too large then debt can matter a lot, even those denominated in a fiat currency, because interest costs compound and grow they can crowd out other national priorities. Growing up your parents may have told you that it’s a lot easier to get into something, then to get out. That is especially true for debt, easy to get in, and painful to get out. Now that we have reached the point where interest payments are over $1 trillion annually, the US has crossed into that uncomfortable territory. The real challenge is to bring debt growth under control without causing a recession or a bout of high inflation. Ray Dalio, a billionaire hedge fund manager who has written books on Why Nations Succeed and Fail, and How Countries go Broke, popularized the idea of a “Beautiful Deleveraging” – a balanced, multi-year process that reduces the painful process of deleveraging when lowering debt burdens through a mix of growth, moderate inflation, controlled austerity, and targeted debt adjustments, rather than a painful deleveraging that could lead to recession, extreme reductions in services, tax increases, and austerity measures. [3][4]

This piece frames what a Beautiful Deleveraging could look like for the United States, why it’s hard, the challenges faced, and how policy could balance the Deflationary forces of tightening with the Inflationary tools sometimes used to ease the adjustment—aiming for a soft landing that improves the country’s long-run fiscal and economic health, while minimizing the pain along the way.

Current Status

- National Debt: The National Debt stands at just over $38 trillion (gross) with over $30 trillion of which is Debt held by the public. [2]

- Deficits: Structural Annual deficits running over $1trillion at around ~6% of GDP. [5][6]

- Interest Costs: Net Interest over $1 trillion annually. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Long-Term Budget Outlook (March 2025), Net Interest reaches 5.4% of GDP by 2055, up from ~3.2% of GDP around 2025. [7][8] Independent analysis by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) highlights a related pressure point: by the 2050s, net interest would consume roughly 28% of federal revenues, absent policy changes. [9]

According to CBO’s latest long-term outlook, by 2055 total Federal outlays (spending) are projected at about 26.6% of GDP, with Net Interest (interest paid on National Debt) near 5.4% of GDP. That means that roughly one-fifth (~20%) of Federal spending will be used to pay interest on the debt. At that scale, interest costs rival or exceed most standalone programs and risk crowding out other priorities if unaddressed. [7][8][9]

What “Beautiful Deleveraging” Means

In Economic terms, Beauty is about reducing debt while avoiding (or at least minimizing) the painful parts of deleveraging and therefore managing that successfully can be Beautiful. Dalio’s Deleveraging framework was originally developed to explain past debt cycles and emphasizes a balanced mix of tools so that the economy can reduce debt without crashing demand and involves these components:

- Spending Restraint (public and private demand constraint),

- Income growth (real GDP growth),

- Debt Restructuring or Terming out (Monetary intervention when necessary), and

- A measured amount of Money/Credit creation (Moderating and managing inflation).

These components, when executed with great skill, political courage, and balance, can help the economy grow enough to ease debt ratios while avoiding a deflationary spiral. [3][4]

For a sovereign like the U.S., that balance translates into a policy with credible fiscal consolidation, productivity-oriented growth policies, and a monetary policy that avoids both runaway inflation and hard-landing deflation. Because the U.S. issues debt in its own currency with deep capital markets, it has more room to maneuver than most, but it is not immune to arithmetic: if interest rates (R) run above growth (G) (See our Article on R > G), debt ratios tend to rise unless deficits are reduced. CBO’s long-term projections foresee precisely this pressure in their future outlook. [9]

Pain Points: Why Deleveraging Is Hard

There is a reason it’s hard, in general large broad spending cuts, and more and higher taxes are not popular. While the components and levers are well known, it takes a healthy amount of political courage to propose policies that maybe unpopular, a great deal of skill and coordination to execute these policies, and likely a good amount of luck and good timing for a sustained period likely across several administrations. A deleveraging can proceed along two of these painful paths, spending cuts and tax increases, and each has tangible real-world consequences:

- Spending cuts: Less public consumption and investment, fewer or slower growth in transfers, and potentially fewer (e.g. program eliminatinos) or lower service levels (e.g., processing times, enforcement, infrastructure maintenance). In macro terms, cuts are deflationary, they reduce aggregate demand, which can cool inflation but also growth and employment in the short run.

- Tax increases: Higher effective tax rates reduce disposable income and/or after-tax returns to investment, is also deflationary. Design matters: broadening the base (fewer exemptions) generally distorts behavior less than steep marginal rate hikes, but either path tightens demand.

Because both mechanisms have a contractionary/deflationary impact and create conditions that can lead to recession, economic hardship, and job loss, a multi-year consolidation approach is part of Dalio’s framework. Instead of a fiscal cliff and extreme austerity based spending cuts; Dalio’s approach phases changes over time; and pairs tighter budgets with growth-friendly policies (innovation, expansion, permitting, skills, productivity increases) that lift the supply side. The goal is to keep nominal GDP growth (real growth + inflation) from collapsing, otherwise debt-to-GDP can rise even while you cut, because the revenue denominator shrinks.

Deleveraging Menu (and Their Trade-offs)

The Tax Project has outlined (See our Article: “Ways Out of Debt”) a non-exhaustive review of policy options to deleverage. Below we provide a summary group them by mechanism. [10]

1) Consolidation via Revenues (Tax Increases)

Summary: Revenue measures (Tax Increases) are deflationary near-term but can be structured to minimize growth drag (e.g., emphasize consumption/external taxes with offsets, or reduce narrow, low-value tax expenditures).

2) Consolidation via Outlays (Spending Cuts)

Summary: Spending cuts can be deflationary; pairing it with supply-side reforms (education/skills, streamlined permitting for productive investment, R&D incentives, labor force productivity growth) can mitigate growth losses and raise potential output over time.

3) Pro-Growth, Supply-Side Reforms (Growth)

Summary: Growth and Supply side reforms (e.g. Productivity, Innovation, Permitting, Energy inputs) that generate real productive growth is the least painful way to lower debt-to-GDP without relying on high inflation.

4) Inflation and Financial Repression (Print Money)

Summary: Modest inflation can ease real debt burdens, part of Dalio’s balance, while managing highly destructive excess inflation. That is why the “beautiful” approach uses only modest inflation alongside real growth, fiscal and monetary management, not inflation as the main lever. [7][9]

The Sooner we Start, the Easier it is

The bottom line is, the longer we wait the harder it gets, the problem will not go away on its own, it only gets worse over time. The 2025 CBO long-term outlook provides a forecast, and it doesn’t paint a great picture:

- Debt Outlook: Debt held by the public rises toward 156% of GDP by 2055, under current-law assumptions. [8][11]

- Outlays vs Revenues: Outlays (spending) climbs from ~23.7% of GDP (2024) to 26.6% (2055); revenues rise more slowly to 19.3% – expanding an already large and persistent structural gap. [8][12]

- Net interest: Reaches 5.4% of GDP by 2055—roughly one-fifth of total federal outlays and around 28% of Federal revenues. [7][8][9]

Those numbers underscore the reason to start now: the later the adjustment, the harder the challenge required to stabilize debt. Conversely, a timely package that the public views as credible and fair can anchor long-term rates lower than otherwise, reducing the interest burden mechanically.

A “Beautiful” U.S. Deleveraging

The Tax Project does not propose or advocate specific policies, however a workable plan using the Dalio Framework would likely include a mix of the following components aimed to stabilize debt-to-GDP within a decade and then bend it downward while sustaining growth and guarding against excessive inflation relapse. A balanced approach:

- A multi-year fiscal framework enacted up front allowing for a ordered and measured deleveraging.

- Credible guardrails: Deficit targets linked to the cycle; a primary-balance path that improves gradually, with automatic triggers to correct slippage.

- Composition: Roughly balanced between base-broadening revenues and spending growth moderation in the largest programs (phased in).

- Quality: Protect high-return public investment; target lower-value spending and tax expenditures first.

- Administration: Resource the revenue authority to improve compliance; align incentives and simplify.

- A growth package to offset the deflationary impulse.

- Supply-side reforms with high ROI: energy and infrastructure permitting; skilled immigration; workforce skills; competition policy that fosters innovation and productivity tools.

- Private-sector: Reduce regulatory frictions that impede capex expenditures in goods and critical infrastructure.

- Monetary-Fiscal Coordination in the background—not Fiscal Dominance.

- Monetary-Fiscal Coordination: The Federal Reserve keeps inflation expectations anchored; it does not finance deficits but it can smooth the adjustment by responding to the real economy and anchoring medium-term inflation near target. Over time, a credible Fiscal policy promoting growth helps bring Rates (R) down toward Growth (G), easing the arithmetic. [7][9]

- Contingency tools (use sparingly)

- “Terming out” Treasury debt Lock in more fixed, long-term loans and rely a bit less on short-term IOUs. Why it helps: If rates rise, less of the debt has to be refinanced right away, so interest costs don’t spike as fast. If the term premium is reasonable and the Fed is in an accommodative stance, shorter term lower rate treasuries maybe attractive to reduce Net Interest expenses.

- Targeted restructuring (not the federal debt—specific borrower groups) Adjust terms for groups where relief prevents bigger damage (e.g., income-based student loan payments, disaster-area mortgage deferrals). Why it helps: Stops small problems from snowballing into defaults and job losses while the government tightens its own budget.

This mix qualifies as “beautiful” by balanacing inflationary and deflationary elements. It shares the burden across levers; it avoids hard financial shocks; it relies primarily on real growth + structural balance rather than high inflation or sudden austerity. Done credibly, long-term rates fall relative to a laissez-faire (do nothing) approach, lowering interest costs directly and via lower risk premia. The country benefits both intermediate (by not inducing a recession and harsh economic measures), and long term freeing up revenue to more productive uses than Debt payments, and supporting growth.

Managing the Macro Balance: Deflation vs Inflation

All this sounds good, but the practical art is to offset deflationary consolidation with pro-growth supply measures, not with high inflation. Consider the balancing act between these different variables:

- Consolidation (deflationary): Fiscal discipline reduces demand, manages structural gaps, good for taming inflation; risky for growth if overdone or badly timed.

- Growth Reforms (disinflationary over time): Expand supply, lower structural inflation pressure; raise real GDP and productivity, improving the debt to GDP ratio.

- Monetary Stance: Should keep inflation expectations managed; if growth softens too much, gradual monetary easing is available if inflation is on target.

- Inflation temptation: Modest inflation can reduce some of the burden mechanically, but leaning on inflation as the adjustment tool can backfire if markets demand higher interest rate (term) premiums; nominal rates can rise more than inflation, worsening R > G and Net interest. CBO’s baseline already shows interest outlays rising markedly even without an inflationary strategy. [7][9]

A “Beautiful Deleveraging“ aims too creates a “soft landing” keeping nominal GDP growth positive, inflation expectations managed, and real growth strong enough that debt-to-GDP falls without creating undue Economic hardships. Managing each of these variables with the often blunt tools available, many of which don’t manifest for months, or years is quite the magic trick, requiring patience, skill, and acumen.

Risks and Pitfalls

The road ahead can be bumpy and full of challenges, managing the risks is key to a successful deleveraging. Here are some areas that can derail a “Beautiful Deleveraging.”

- Front-loaded austerity that slams demand into a downturn or recession; a gradual path anchored by rules and automatic stabilizers is safer and creates less hardships. It means that we will endure less pain over a longer period. Some may want to rip the band aid off and take the measures all at once.

- Policy whiplash (frequent reversals) that destroys credibility and raises risk premia (higher Interest rates); stable consistent policies beat one-off “grand bargains” and political vacillations.

- Over-reliance on rosy outlooks; plans should make conservative growth assumptions, and reasonable baselines.

- “Kicking the can” down the road with laissez-faire policies until interest dominates the budget, leaving painful, crisis-style adjustments as the only option is the biggest of all the Risks. CBO’s outlooks illustrates how waiting raises the eventual cost, and negative consequences. [7][8][9]

Is it Worth it?

On the surface, that’s an easy question, however the answer may pit generations against each other each with their own point of view and different perspectives. Current generations at or near retirement who may not see the worst effects of a laissez-faire policy may see the risk of recession, and cut backs in service as an unacceptable change to their Social Contract which they may have worked a lifetime under a set of expectations that they counted on. Younger generations, may see it as generational theft, placing an undue burden on them for debt they had little or no part in creating. Both are valid perspectives, however, the long term effects of a “Beautiful Deleveraging” will deliver these positive durable payoffs for the Country:

- Out of Doom Loop: High debt is a trap, as out of control interest expenses rise, debt grows and the gap between revenue and debt rises in a self reinforcing doom loop. Breaking that loop is key to a healthy economy.

- Lower Interest burden: As debt drops, so does Net Interest expenses. Instead of crowding out other expenses, revenue is freed up to other National Priorities (e.g. Healthcare, Education, Infrastructure, Social Services, Surplus, Sovereign Wealth). [7][9]

- Greater Macro resilience: With manageable debt exogenic shocks, pandemics, wars, financial events, give the Government financial space to manage these events without taking on negative levels of debt.

- Higher Trend growth: When consolidation is paired with genuine productivity reforms, lower debt ratios are correlated with higher growth, supporting living standards and the tax base. [14][15][16]

Summary

A “Beautiful Deleveraging” is but one way to approach the intractable problem of high debt. It represents a reasonable approach that balances near term realities with long term impacts. Our choices now will define the America of the future, and the quality of life younger Americans will have and future generations will inherit. Will it be painless? Probably not, it will likely require some sacrifice and discipline. The challenge wasn’t created in a short period, and it won’t be solved in a short period. Is it achievable? If we face the truth with candor about trade-offs, accept phased steps that the public deems fair, and have a bias toward investments that raise long-term productive capacity, than it is possible. The biggest question is the will of the American people. That, more than any single policy, will determine our future. At the Tax Project we will always bet on informed Citizens making the best choices for America – we will always bet on America. That defines the essence of a “Beautiful Deleveraging.” [3][4][10]

Citations

[1] U.S. Department of the Treasury, America’s Finance Guide: National Debt (accessed Oct. 2025): “The federal government currently has $37.98 trillion in federal debt.” (fiscaldata.treasury.gov)

[2] Joint Economic Committee (JEC) Debt Dashboard (as of Oct. 3, 2025): Gross debt ~$37.85T; public ~$30.28T; intragovernmental ~$7.57T. (jec.senate.gov)

[3] Ray Dalio, What Is a “Beautiful Deleveraging?” (video explainer). (youtube.com)

[4] Ray Dalio, short-form clip on “beautiful deleveraging.” (youtube.com)

[5] Reuters coverage of CBO near-term deficit path (FY2024-2025). (reuters.com)

[6] Associated Press summary of CBO’s 10-year outlook (debt +$23.9T over decade; drivers). (apnews.com)

[7] Congressional Budget Office, The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055—headline results: net interest 5.4% of GDP by 2055; outlays path. (cbo.gov)

[8] Peter G. Peterson Foundation, summary of the 2025 Long-Term Outlook: outlays to 26.6% of GDP; interest path and historical context. (pgpf.org)

[9] Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), analysis of CBO 2025 outlook: interest consumes ~28% of revenues by 2055; R > G later in the horizon. (crfb.org)

[10] Tax Project Institute, Ways Out of Debt: US Options for National Debt (June 14, 2025). (taxproject.org)

[11] Reuters recap of CBO long-term debt ratio (public debt ~156% of GDP by 2055). (reuters.com)

[12] CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035 (context for near-term path). (cbo.gov)

[13] Ray Dalio, What is a Beautiful Deleveraging? https://youtu.be/wI0bUuQJN3s

[14] Kumar, M. S., & Woo, J. (2010). Public Debt and Growth (IMF Working Paper WP/10/174). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781455201853.001

[15] Cecchetti, S. G., Mohanty, M. S., & Zampolli, F. (2011). The Real Effects of Debt (BIS Working Paper No. 352). Bank for International Settlements.

[16] Eberhardt, M., & Presbitero, A. F. (2015). Public debt and growth: Heterogeneity and non-linearity. Journal of International Economics, 97(1), 45-58.