The curious case of Beardsley Ruml

The United States in the mid-1940s, the country had just financed the most expensive and bloody war in history. Something new is occurring: paychecks for the first time begin withholding income tax out of those paychecks as they are earned. The so called “Gold Standard” where Gold backs every dollar as a legal promise is gone for Americans. The Federal Reserve is learning how to steer interest rates for a peacetime economy. Beardsley Ruml, a former Macy’s finance chief turned New York Federal Reserve chair steps into this backdrop and writes an article in the January 1946 American Affairs publication with a simple but provocative statement:

“Taxes for revenue are obsolete.”

Beardsley Ruml

He isn’t trolling – he meant what he said. He’s telling readers that the way money works has changed, and if we keep thinking about Federal taxes like a family checking account, “first earn, then spend”, we misunderstand how money works in a fiat currency not backed by a hard asset (like gold) and what taxes actually do in a monetary system. The government no longer needs to wait for tax revenue to spend. Stop for a second and think about this statement, it is a Matrix like moment where Morpheus asks Neo if he wants the Red Pill or the Blue Pill. The Red Pill represents the truth and how fiat currency actually works, and the Blue Pill represents just ignoring the truth and going back to your comfortable understanding of how money works. A full copy of Ruml’s Thesis can be found here.

Fiat currency is money that is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver, but is instead backed by the government that issued it. Its value comes from the public’s trust and the government’s authority, which decrees it as legal tender. Examples of fiat currency include the U.S. Dollar, the European Union’s Euro, and the Japanese yen.

The Backdrop for Ruml’s Thesis

When Beardsley Ruml wrote “Taxes for Revenue Are Obsolete,” he was synthesizing his experiences of how American money actually worked, and the changes going on around him. As a Federal Reserve chair, participant in Bretton Woods, and someone who shaped policy, like Pay as you go payroll, he had a first hand view.

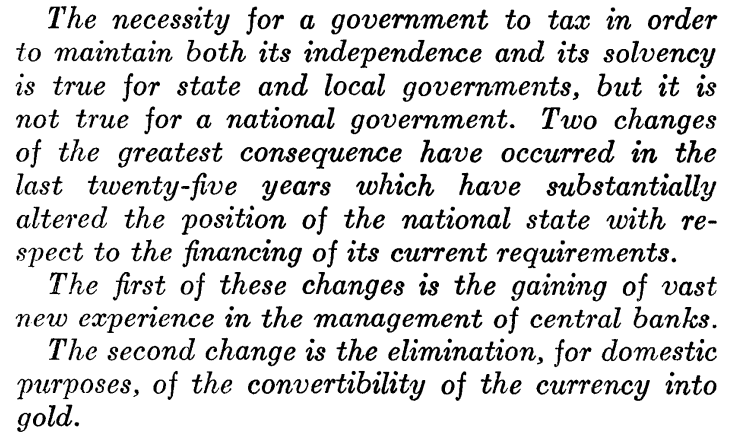

1933–1934: Off domestic gold—constraint shifts inside the border

In the early New Deal years, the U.S. ended domestic gold convertibility and reorganized the gold regime under the Gold Reserve Act. Inside the country, dollars were no longer legally IOUs for a fixed weight of metal. The binding constraint on federal finance began to migrate from gold reserves to inflation, real capacity, and statute (law). Ruml’s essay explicitly ties his thesis to this inconvertible-currency reality: a national state “with a central banking system… [whose] currency is not convertible into any commodity.” [1]

“Final freedom from the domestic money market exists… where [there is] a modern central bank, and [the] currency is… not convertible into gold.” [1]

1942–1943: Pay-as-you-go withholding—taxes become continuous

With wartime employment booming, Ruml helped push paycheck withholding (the Current Tax Payment Act of 1943), turning the income tax from an April settlement into a real-time flow. Withholding didn’t just improve administration; it made taxes a live instrument for managing purchasing power across the year, reinforcing Ruml’s view that taxes should be judged by effects—on prices, distribution, and behavior rather than as a cash bucket to “fund” future outlays (spending). [5]

1944–1946: Bretton Woods and the New York Fed vantage point

As Bretton Woods took shape (par exchange rates, gold convertibility for foreign official holders, capital controls), Ruml was chairman of the New York Fed (wartime through 1946). He watched the Fed support Treasury borrowing for war finance and then toward peacetime normalization. In that setting, Ruml saw operationally how Treasury spending settled through the Federal Reserve, and how taxes and bond sales later lowered purchasing power and supported interest-rate control. He previewed his thesis in a 1945 address and then published the 1946 essay, sharpening the claim that taxes are essential for what they do, not to generate revenue before spending. [1]

“All federal taxes must meet the test of public policy and practical effect.” [1]

1951: The Treasury–Fed Accord—roles clarified

Ruml’s essay was given before the Treasury–Fed Accord, but the Accord (1951) confirmed the institutional direction he was pointing toward: monetary-policy independence to target rates and prices, separate from Treasury’s debt-management imperatives. After pegging wartime yields, the Fed reclaimed the ability to resist fiscal pressure when inflation called for tighter settings—strengthening the case that budgets should be judged by employment, prices, and distribution, not balanced-budget rituals. [3]

1971–1973: Nixon ends dollar–gold convertibility—Ruml’s logic matures ex-post

Ruml died in 1960, but his logic became even more straightforward after Nixon suspended official dollar–gold convertibility and major currencies moved to floating exchange rates. From then on, the United States was unambiguously a fiat-currency issuer: spending cleared through the Fed first; taxes and bond sales followed to manage inflation, distribution, market structure, and interest rates. Ruml’s once-provocative line read less like heresy and more like a plain description of operations—with the real constraints now fully on inflation, capacity, and institutional credibility. [4]

“The public purpose… should never be obscured in a tax program under the mask of raising revenue.” [1]

So the events and experiences: moving internally away from gold backed assets at home (1933–34), real-time taxation (1943), Fed Monetary Autonomy (1951), and externally away from gold (1971–73) together explain how Ruml could say, without gimmicks, that taxes are essential for what they do: price stability, distribution, behavior, and currency demand—rather than as a prerequisite to spend. He believed the question for any program was: Can the real economy deliver, and how will policy manage the price-and-capacity path along the way? [1][3][4][5]

Follow the dollar: how “mark-up” works

To see understand Ruml’s Thesis more concretely, we can use by example a single payment.

A federal contractor finishes a bridge repair job. Treasury authorizes payment to the contractor. The Federal Reserve, which is the government’s bank, marks up the contractor’s checking account at their commercial bank. Two things happen at once:

- The contractor’s deposit goes up (their balance goes up, they have more spendable money).

- The contractor’s commercial bank’s reserve balance at the Fed goes up (the bank’s settlement cash).

No one at the IRS had to collect that exact amount yesterday for this payment to clear today. In other words, the government did not have to wait for revenue before spending. The payment clears because the United States operates the dollar system. Once that payment is made, taxes later can remove some of those dollars from private hands; and bond sales can swap some deposits/reserves for Treasury securities to help the Fed keep interest rates where it wants them.

That’s the basics of Ruml’s claim. In a fiat system with a central bank, spending isn’t bottlenecked by prior tax receipts. The real limits are inflation and real capacity – how many workers, machines, homes, kilowatts, and microchips the economy actually has.

“Federal taxes can be made to serve four principal purposes…” [1]

Ruml’s Four Functions for federal taxes then are as follows:

- Price stability (control inflation by removing purchasing power when the economy runs hot)

- Distribution (redistributing wealth (purchasing power) based on policy)

- Behavior/structure (altering behavior with economic incentives e.g. carbon, tobacco, alcohol, etc.)

- Currency demand/legitimacy (creating demand for currency by requiring Federal taxes be paid in Dollars)

Questions from Ruml’s thesis

Not only was Ruml’s thesis provocative, if true it brings up a whole set of new questions, and challenges a lot of our notions of money and taxes.

Question: If spending can come before tax revenue, and the government doesn’t need it to spend, why are we paying taxes at all?

This is the heart of Ruml’s Thesis, that while the government did not need taxes to allow the government funding to spend, taxes did play an important role. Ruml believed taxes were a way to manage price stability (inflation): they help keep prices in check by reducing purchasing power (demand), they shape who holds purchasing power, and they anchor the currency by requiring dollars to settle tax bills. Without taxes, you could spend for a time but you would lose price stability and the public’s confidence in the stability of the dollar itself.

Question: Why do politicians still ask “How will you pay for it?” if taxes aren’t needed to spend?

Because you hit walls long before you “run out of money”:

- You can’t print money for Imports. If spending weakens the value of the dollar, import prices jump or supplies dry up. That impacts living standards fast. [18][19][20]

- Boom–bust finance. Prolonged easy fiscal + easy money can inflate asset and credit bubbles; when they pop, banks retrench and recessions deepen—costlier than using modest drains (purchasing power reductions) earlier. [9]

- Tax-base erosion (seigniorage limit). If people expect rising prices and weak policy response, they flee into hard assets/FX; real tax intake falls just when control is needed (seen in hyperinflations). [16][17]

- Real-world choke points. Money doesn’t increase productivity, create nurses, build cars, ports, or grid lines; increasing demand into bottlenecks yields price instability, not output. [10][12][13][14]

- Interest-cost feedback. Rate hikes to cool inflation raise government interest bills, shifting income toward bondholders and forcing tougher trade-offs later. [11][9]

- Predictable Policy keep costs low. Predictable authorizing/phase-out rules lower risk and support long-term contracts; junk the rules and borrowing costs/investment worsen even before inflation moves. [11][9]

Ruml’s point isn’t spend in excess, it’s that taxes aren’t required to spend. Taxes and pacing are the governors that keep prices stable, protect access to vital imports, prevent financial bubbles, and align demand with what the real economy can actually deliver. [1][2][3][6][7]

Question: Why not just make everyone a billionaire?

This is an interesting thought exercise, if everyone was a billionaire would the purchasing power of the currency be the same? Since money is a claim on real output, not actual output (productivity) if everyone was a billionaire most certainly the purchasing power of the fiat currency would be substantially lower. More money without more productivity (nurses, houses, energy, widgets, etc.) brings higher prices (inflation), not greater prosperity. Ruml’s thesis keeps taxes (and other monetary mechanisms to reduce purchasing power) in the toolkit precisely to match purchasing power to capacity.

Japan: Use Case and cautionary tale

Japan is the cleanest real-world test of part of Ruml’s thesis. For decades, Japan’s gross public debt sat well above 200% of GDP—yet long-term interest rates were near zero under Bank of Japan (BOJ) policy. The Yen has had no solvency crisis, of major uncontrolled inflation. That supports Ruml’s point that a nation which issues debt in its own currency faces inflation and capacity constraints more than a “running out of money” constraint [12][13].

However, during the same period shows why Ruml’s mechanics don’t solve the growth problem by themselves:

- The “lost decades.” Japan endured a multi decade stretch of weak real growth and disinflation/deflation. Even with easy financing conditions Japan was not able to create growth and productivity improvements or new sectors on their own [14][16].

- Balance-sheet hangover. After the 1990s asset bust, households and firms deleveraged for years—private demand stayed weak even when public deficits filled part of the gap.

- Wages and demographics. An aging population, shrinking workforce, and corporate practices contributed to sluggish productivity and flat real wages for many workers [14][16].

- Foreign Exchange (FX) and imported prices. Episodes of yen weakness raised import costs (notably energy), squeezing households and complicating the path out of very low inflation.

- Policy evolution. The BOJ cycled through low rates including zero and even negative interest rates for 8 years!, Quantitative Easing, and yield-curve control, then gradual adjustments. These tools stabilized finance but didn’t create robust growth, reminding us that supply-side capacity (energy, housing, innovation, corporate reform) still determines living standards.

Monetary sovereignty may avoid immediate solvency issues in your own currency, but prosperity still depends on productivity, demographics, and the supply side. The policy art isn’t printing more money; it’s about managing the balance between demand and capacity so money meets output rather than outruns it. [12][14][16]

Where Ruml’s Thesis fails

Ruml presumes monetary sovereignty – you tax and spend in your own currency, with credible institutions, and you don’t owe large amounts in someone else’s money, or require external inputs like energy, food, or other goods and raw materials. It also assumes you don’t outspend the productive capacity of the country. If and when those conditions vanish, significant and detrimental impacts could fall upon the country. There are a number of examples of hyper inflation, that have damaged the economic and well being of countries.

- Weimar Republic Germany (1921–23). Huge reparation obligations (external), political fracture, and aggressive central-bank financing into a collapsing anchor produced hyperinflation. The issue wasn’t “deficits” in the abstract; it was external liabilities + institutional breakdown + supply dislocation [18].

- Zimbabwe (2000s). Radical output collapse (agriculture and supply chains), governance failures, and money creation against shrinking real capacity drove prices into hyperinflation. Too many nominal claims, too little real output [19].

- Sri Lanka (2022). A foreign-currency crisis: depleted FX reserves, weak tax base, and large hard-currency debts. You cannot print your own fiat money when your liabilities are in dollars/euros; the constraint becomes imports and external financing, not domestic “solvency” [20][21][22].

Ruml’s Thesis exists when you issue your own currency, are not dependent on externalities or foreign debt, and spending does not outpace productive capacity and credibility in currency is maintained. Lose those – and inflation, devaluation, and/or default can take the driver’s seat.

How most Economists think about Ruml’s Thesis

Most modern economists agree on the operational basics: in a fiat currency system, the Treasury and central bank can ensure payments clear in the home currency; taxes/bonds then drain purchasing power and help the central bank hit an interest-rate target. That’s not controversial [6].

Where Economists caution starts – real life, not the textbook:

- Prices can jump if demand outruns supply.

If new spending hits an economy short on cars, nurses, chips, or houses, prices rise. That happened in 2020–22 during the COVID Pandemic: demand recovered while supply was jammed. Changing taxes or budgets is slow, so economists like built-in brakes (automatic stabilizers) and phased rollouts. [6][7][2] - Higher interest rates make debt cost more.

The U.S. can always pay in dollars, but when the Fed hikes to fight inflation, the interest bill on government debt climbs. If that bill grows faster than the economy or tax revenue, Congress faces tougher trade-offs. Last year Net Interest on the US National Debt was over $1 trillion. The 1951 Accord exists so the Fed can fight inflation even if it makes borrowing costlier. [3][10][11] - Consumer Sentiment and Beliefs matter.

Prices stay more stable when people trust leaders will cool inflation off if needed. If policy looks like “spend without limits,” businesses and workers build in higher inflation into their cost models and pass that along, and it’s harder to bring back down once its gone up. - Not every side effect shows up in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Inflation can manifest itself in many ways that trickle down to the ordinary consumer in ways that aren’t tracked well by major indexes like the CPI. Big deficits with low rates can push up stock and house prices and widen wealth gaps, even if everyday inflation isn’t high. That can erode support for useful programs. [10] - At full tilt, something has to give.

When the economy is already near full capacity, more public spending creates demand that competes with private demand for the same workers, resources, and materials. The result isn’t “no money”; it’s higher prices or shifting resources away from something else. This can be managed with taxes destroying demand, phased timing reducing demand peaks, or adding supply. - America, and most countries are deeply intwined in Global Trade

We import energy, food, critical resources, and key parts from a Global Supply chain. If the dollar weakens or suppliers get nervous, import prices rise and shortages can appear. Building domestic capacity (energy, logistics, housing) and self sufficiency can offset that, but it also comes at a cost.

Where Economists actually stand on Ruml’s thesis

- Broad agreement on the plumbing: Most economists accept that in a fiat system the government can pay first in its own currency, and that taxes/bonds are tools to manage demand and interest rates. That’s mainstream (see the Bank of England explainer). [6][7]

- Support for using deficits in slumps: In recessions or emergencies, many economists favor deficit spending to protect jobs and speed recovery. (Ruml’s taxes aren’t required for spending fits this.) [6][7]

- Caution about pushing it too far: Many are wary of treating “spend first” as a green light without a clear plan for inflation, ensuring demand doesn’t outpace supply and productive capacity, and the outside world (Global trade, key economic inputs from outside the U.S.). They stress guardrails, automatic stabilizers, and credible roles for the Fed and Congress (the spirit of the 1951 Accord). [3][10][11]

- Split on the stronger claims (often linked to MMT):

- Critics say relying mainly on taxes to stop inflation is too slow and political, and they worry about fiscal dominance (pressuring the Fed to accommodate debt). They also flag open-economy risks and asset-price side effects. [9]

- Supporters respond that good design (automatic tax/benefit adjusters, phasing, targeted drains) can handle those issues, and that recognizing the fiat mechanics helps us focus on real limits (people, machines, energy) rather than imaginary cash limits. [9]

Economist View Summary:

- They mostly agree on the mechanics.

- They agree deficits can be useful tools.

- They differ on how far you can push spending before you risk inflation, financial stress, or FX problems

- They differ on whether taxes can be used quickly and fairly enough to cool inflation off. [6][7][3][10][11][9]

A Ruml-style way to judge any Spending program

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost and budget impact of programs. Using a Ruml Thesis style way to evaluate programs might look something like this.

- Capacity: Do we have the people, skills, materials, energy, and productive capacity? If not, what’s the plan to expand supply?

- Inflation plan: If demand overheats, what automatic brakes kick in—phasing, adjustable credits, temporary surtaxes? [2]

- Distribution: Who gets the new purchasing power and who gives something up?

- External exposure: Are we import or FX sensitive in the relevant inputs? Do we hold external exposures?

- Institutional alignment: Are fiscal choices made with a central bank focused on price stability (the post-1951 lesson)? [3]

Summary: Ruml’s answer to the question

In summary we ask the title question: “Are taxes needed,?” Ruml’s answer—in his own words—is that their revenue role is not the point in a fiat system:

“Taxes for revenue are obsolete.” [1]

They are needed for what they do: to keep prices stable, shape distribution and behavior, and anchor demand for the dollar:

“Federal taxes can be made to serve four principal purposes…” [1]

And the standard for judging them is not myth or ritual but outcomes:

“All federal taxes must meet the test of public policy and practical effect.” [1]

Read that together and you have the summary of his thesis: the United States does not tax so that it can spend; it taxes so that the money it spends produces stable prices, fair distribution, incent certain behaviors, and ensure a credible currency. While his beliefs were provocative at the time, and still controversial, the mechanics of his thesis remain true and you can see his influences in the roots of Neo Chartalism, Functional Finance and all the way to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) today.

References

[1] Ruml, B. (1946). Taxes for revenue are obsolete. American Affairs, 8(1), 35–39. https://billmitchell.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/taxes-for-revenue-are-obsolete.pdf

[2] Lerner, A. P. (1943). Functional finance and the federal debt. Social Research, 10(1), 38–51. https://public.econ.duke.edu/~kdh9/Courses/Graduate%20Macro%20History/Readings-1/Lerner%20Functional%20Finance.pdf

[3] Federal Reserve History. (n.d.). The Treasury–Fed Accord (1951). https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/treasury-fed-accord

[4] Federal Reserve History; U.S. State Dept. Nixon ends convertibility of U.S. dollars to gold (1971); The end of Bretton Woods (1971–73). https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/gold-convertibility-ends ; https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock

[5] IRS; Senate Finance Committee. Current Tax Payment Act of 1943—historical highlight & legislative history. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/historical-highlights-of-the-irs ; https://www.finance.senate.gov/download/1946/03/04/legislative-history-of-the-current-tax-payment-act-of-1943

[6] Bank of England. (2014). Money creation in the modern economy. Quarterly Bulletin Q1. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

[7] IMF. Back to Basics: What is inflation? (2010/2018). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2010/03/basics.htm ; https://www.imf.org/en/Videos/view?vid=5727378902001

[8] American Affairs (1946). Vol. VIII, Jan. 1946—table of contents with Ruml entry. https://cdn.mises.org/AA1946_VIII_1_2.pdf

[9] Brookings; Cato; Levy Institute. Debates on MMT and fiscal capacity. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/is-modern-monetary-theory-too-good-to-be-true/ ; https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2019/modern-monetary-theory-critique ; https://www.levyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/wp_996.pdf

[10] World Bank; BOJ; IMF/press for Japan context (growth, debt, prices, yen). https://data.worldbank.org ; https://www.boj.or.jp/en/ ; representative coverage e.g., AP (Feb 2024): https://apnews.com/article/893d53deba654c4924e4924f0b321cc5

[18] Brunnermeier, M. K., et al. (2023). The debt-inflation channel of the German hyperinflation (working paper synopsis). https://markus.scholar.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf2651/files/documents/Hyperinflation_Weimar_Germany.pdf

[19] Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. (n.d.). Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe (backgrounder). https://gdsnet.org/ZimbabweHyperInflationDallasFed.pdf

[20] IMF. (2025, Jun.). Lessons from Sri Lanka’s recovery and debt restructuring (speech/news). https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2025/06/16/sp061625-gg-this-time-must-be-different-lessons-from-sri-lankas-recovery-and-debt-restructuring

[21] Reuters. (2024, Apr.). World Bank raises Sri Lanka growth forecast. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/world-bank-raises-sri-lankas-growth-forecast-22-2024-04-02/

[22] Reuters. (2025, Mar.). Sri Lanka clinches debt deal with Japan. https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/sri-lanka-clinches-deal-with-japan-restructure-25-billion-debt-2025-03-07/Full Text