What is the Tax Gap?

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) uses the term Tax Gap to describe the difference between (1) the amount of tax that should be paid under the law for a given year and (2) the amount of tax that is actually paid. The IRS calls the first concept “True Tax Liability.” The Tax Gap is used by the IRS as a compliance measurement, intended to quantify how much legally owed tax is not collected. [1]

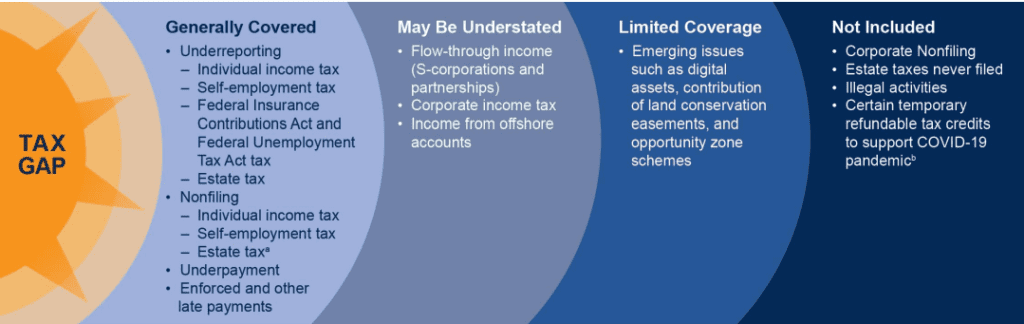

The Tax Gap is often discussed as if it were a single, objectively identified pool of “missing money.” It is not. The Tax Gap is an estimate, based on direct and estimated assessments of missing revenue. What can be directly observed at scale is what taxpayers report and what they pay, both on time and later. What cannot be directly observed at scale, and hence estimated, is “True Tax Liability” for every taxpayer absent intensive verification. That distinction matters because the Tax Gap is built by combining observed payment/reporting data with audit programs, statistical inference, and projections. It is a useful tool, but it is not equivalent to a ledger of collectible receivables. [1][4] While it is entirely likely that some of the non directly observed amount is in fact a true liability owed by tax payers, how much of the figure is up for debate.

How the IRS estimates the Tax Gap

The IRS does not produce Tax Gap estimates in real time. The estimates are developed in study windows and released with a time lag, reflecting the time required to assemble data, conduct audit-based measurement programs, and model components that are not fully observable. As a result, “the latest tax gap” should be read as the latest official estimate for a particular tax year or tax-year range, not as a current-year dashboard. [1][2]

This lag structure also means year-to-year changes in the reported tax gap may reflect changes in underlying compliance behavior, but may also reflect changes in measurement methods, audit coverage, data availability, and economic composition. The Government Accounting Office (GAO), understanding the limits of what is directly observable, has emphasized the importance of continued methodological improvement and transparency in how these estimates are constructed. [4]

Headline versus Reality

Increasingly common in current political dialogue, the Tax Gap is used as a fixed accounting number that “we just need to collect.” This article will explain the Tax Gap, and why the “no brainer” misconception that we can “just collect the tax gap” is incomplete and potentially misleading. As an estimate based on non directly observed data, it is best thought of as a conceptual framework useful in discussions of efficiency, and potential opportunity and not as a true accounting liability. Before we try to use it as a metric, it is necessary to understand what the IRS means by the Tax Gap, what portion is expected to be recovered anyway, and where the largest uncertainties and constraints arise.

“Imagine what we could do for people with $7 trillion.”

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) [11]

Gross vs Net: IRS “not paid on time” vs. “never paid”

The IRS reports the tax gap in two related forms:

- Gross Tax Gap: the amount of tax liability that is not paid voluntarily and on time. [1]

- Net Tax Gap: the portion of the Gross Tax Gap that the IRS projects will remain unpaid after accounting for what is eventually paid through late payments and enforcement. [2]

The difference between the two is critical. It is the IRS’s estimate of the amount that will be recovered after the deadline through enforcement and other late payments. [2] For Tax Year 2022, the IRS estimated:

- Gross Tax Gap: $696 billion

- Net Tax Gap: $606 billion

- Enforced and Other Late payments delta: $90 billion [2]

This Gross-to-Net adjustment is the first major “Headline vs Reality” issue. Public discussion often treats the gross number as if it were the amount available to be collected with additional enforcement. The IRS’s own framework explicitly says otherwise: a portion is expected to arrive later, and a large residual is expected not to arrive. [2]

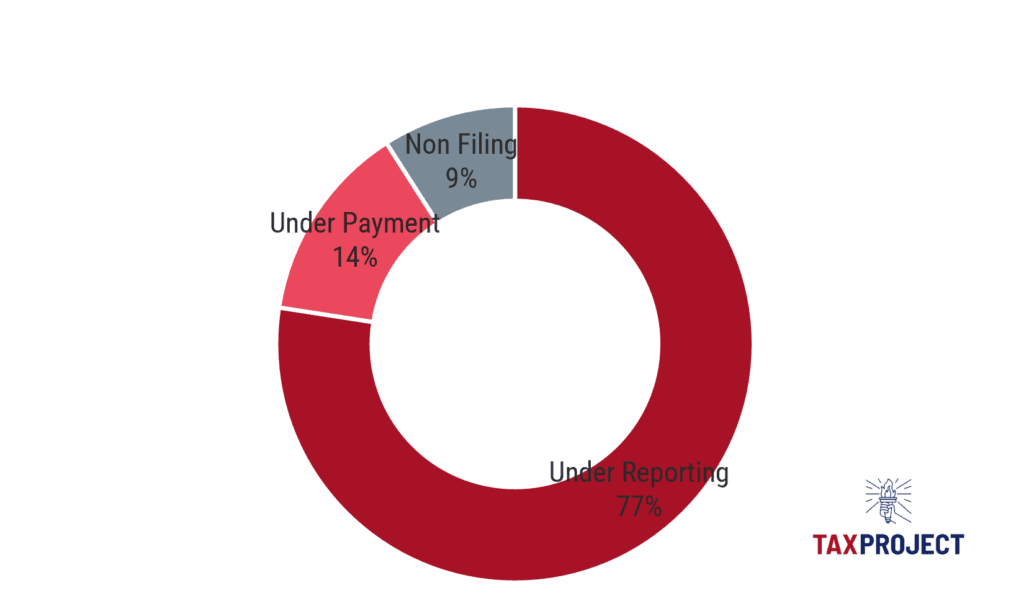

The Tax Gap Components

To understand where the Tax Gap comes from and why it is not simply a matter of “trying harder” the IRS decomposes the Gross Tax Gap into three categories:

- Non Filing: required returns not filed.

- Under Reporting: returns filed but the Tax liability is understated.

- Under Payment: returns filed with correct reported liability, but taxes not paid in full on time. [2]

A Treasury Financial Report excerpt summarizing the Tax Year 2022 projections reports the gross gap as $696.0B, comprised of Non Filing ($63.0B), Under Reporting ($539.0B), and Under Payment ($94.0B) (See Figure 1). [3]

These categories represent distinct levels of observability (and hence reliability), liability from an accounting perspective, and they behave differently with respect to enforcement effort often rising significantly the more you try to collect.

Non Filing: a detection problem before a collections problem

Non Filing is frequently discussed as if it were merely a matter of pursuing known delinquencies. In practice, Non Filing is often a detection and identification problem. When a person’s income and activity are captured through strong third-party reporting (for example, routine wage reporting), Non Filing is more readily discoverable. Where reporting is limited or activities are less legible to the system, like small and independent businesses, discovery becomes more resource-intensive and uncertain.

Under Reporting: the largest category and the least directly observable

Under Reporting is the largest component of the Tax Gap, and it is also the most dependent on estimation. Under Reporting spans a wide range of situations: simple misstatements, ambiguous interpretations, valuation disputes, and complex structures. [3][4]

Because “true liability” is not directly observable for most underreporting cases, the IRS uses audit-based programs and statistical methods to estimate the magnitude of underreporting and then adjusts for noncompliance that audits are expected to miss (“undetected” noncompliance). The GAO has examined these methods and urged continued steps to strengthen and improve Tax Gap estimation. [4]

This is one of the central reasons the tax gap is not identical to a known pool of collectible balances. A portion of the underreporting estimate is an inference about what is not seen, not a list of identified cases of actual liability awaiting collection.

Underpayment: where collectability constraints are unavoidable

Underpayment is closest to what the public imagines as “money owed but not paid.” It refers to taxes reported on returns that are not fully paid on time. [2] This category highlights the most basic constraint on “just collect it”: assessments and enforcement actions do not guarantee collection, particularly where taxpayers lack the money (liquidity or solvency) to pay.

Measured versus Estimated

The Tax Gap combines observed data with inferred quantities.

On the observed side, the government can directly measure:

- What is paid on time

- What is paid late

- What is collected through enforcement [1][2]

On the inferred side, the government must estimate true liability, especially for Under Reporting, by combining audit results, third-party reporting, and statistical adjustments. [4] The IRS also notes that estimates for more recent tax years require greater reliance on forecasts for eventual late and enforced payments because fewer years of post-filing payment history are available. [2]

This is why the Tax Gap should be read with two simultaneous interpretations:

- It is an important conceptual compliance benchmark to identify opportunities.

- It is not a fully observed accounting liability, fully collectible stock of “missed revenue.”

Once that is understood, the “no brainer” claim begins to look less like a plan and more like a slogan.

International comparisons challenges

Most countries have some Tax Gap in their collections. Seemingly this would be a straight forward way to check the effectiveness of Government collection efforts. However, Tax gap comparisons across countries are frequently apples-to-oranges, for a structural reason: jurisdictions do not necessarily measure the same types/concepts.

A common example is comparing a whole-system compliance estimate to a single-tax gap such as a Value Added Tax (VAT) gap. The European Commission’s VAT Gap is explicitly about VAT, not about the full tax system. [5] Different tax mixes, different reporting regimes, and different denominators further complicate comparisons.

This does not mean international comparisons are impossible; it means they require careful alignment. Like-with-like comparisons (VAT-to-VAT, income-tax-to-income-tax, or genuinely harmonized “percent of theoretical liability” metrics) are informative. Casual rankings built from mismatched definitions are not. [5]

Enforcement Economics: Diminishing Returns

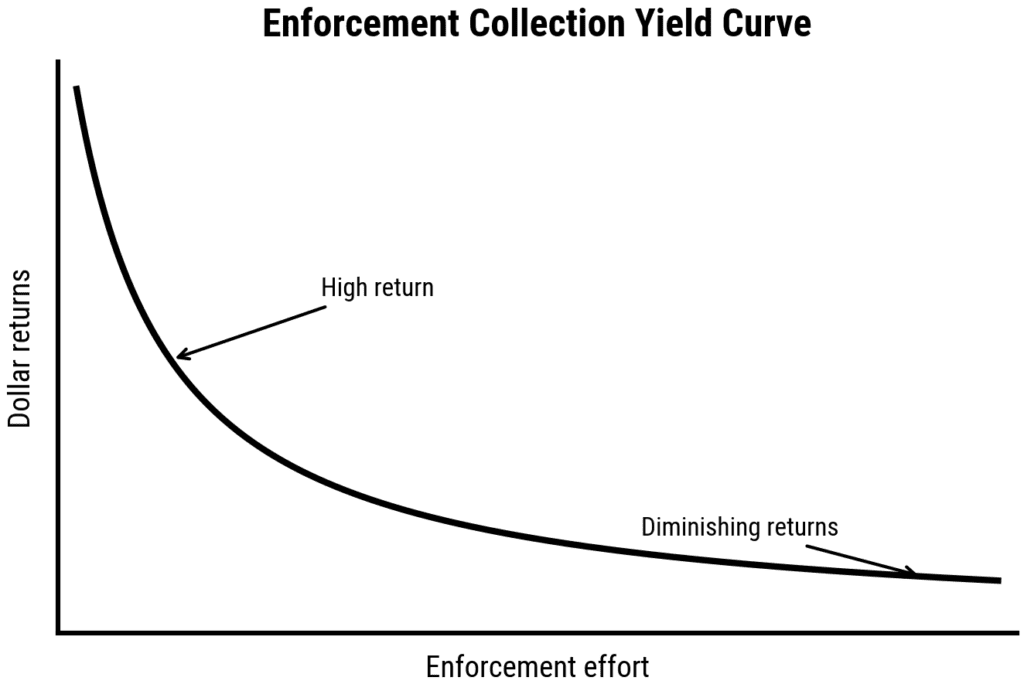

The political shorthand that “enforcement pays for itself” is not inherently wrong; targeted enforcement initiatives can yield substantial revenue. The problem is treating a high marginal return as a constant that can be scaled to close the entire gap.

Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew was quoted in 2013 saying IRS enforcement spending yields $6 for every $1 spent. [6] Whether that ratio is accurate for particular initiatives at particular times, it does not follow that the same ratio holds as a general average across a large-scale enforcement expansion aimed at the full tax gap.

Tax Collection in terms of effort is much like cycling. The amount of effort used while you are going slow is easy, and as you gain speed the amount of effort, and resistance due to wind increases. Each increase is a leap in effort requiring exponentially more effort with each leap. Such is Tax Collection, as collection efforts extend into the long tail—smaller balances, weaker ability to pay, more complicated circumstances collection can become progressively more expensive per dollar recovered. This is a practical constraint that no amount of rhetoric can repeal. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) models this into their estimates as the effort increases, the return in revenue drops the more you attempt to collect.

“Thus, in CBO’s estimates, the ROI drops by 10 percent for every 10 percent increase in spending for enforcement and related activities increases”

Congressional Budget Office [7]

CBO explicitly models diminishing returns in enforcement funding. In discussing how changes in IRS funding affect revenues, CBO states that ROI declines as spending for enforcement and related activities increases, providing a rule-of-thumb: ROI drops by 10 percent for every 10 percent increase in enforcement and related spending over baseline. [7]

This modeling choice captures a basic reality: the easiest dollars to collect are collected first. As enforcement expands, agencies move from high-yield opportunities (clear mismatches, strong evidence, high collectability) toward lower-yield opportunities (complex cases, ambiguous positions, weaker collectability, higher dispute and administrative costs). A reasonable way to visualize this is an “enforcement yield curve” where the marginal revenue per enforcement dollar declines as enforcement scales, eventually approaching a low-return tail. (See Figure 3)

The IRS’s own net tax gap concept implicitly reflects this kind of asymptote. Even after late payments and enforcement, the IRS projects a substantial residual remains unpaid. [2]

Biden-era IRS Funding Push

The Inflation Reduction Act provided a major multi-year increase in IRS funding. The public debate often framed this as a means to substantially reduce the Tax Gap, sometimes implying that large sums could be recovered through enforcement and modernization. [8]

In February 2024, Treasury stated that the IRA’s IRS investments would increase revenue by as much as $561 billion over 2024-2034 and cited IRS analysis supporting higher revenue projections than earlier estimates. [8][9] CBO’s general approach, however, is to treat enforcement returns as diminishing and to score them conservatively relative to more optimistic agency scenarios. [7]

The practical interpretation is not that one side is necessarily acting in bad faith. It is that “closing the Tax Gap” is not a mechanical exercise where spending scales linearly into revenue. It is a system where observability limits, administrative capacity, disputes, collectability, and behavioral response create declining marginal returns.

Second & Third Order Effects: avoidance and adaptation

Enforcement is not conducted in a vacuum. When enforcement intensity increases, taxpayers respond. Some responses are lawful, changes in timing, restructuring entities, choosing different tax treatments. Others are unlawful, substitution into less observable forms of evasion. Still others show up as real resource costs—higher compliance spending, higher administrative burden, and greater dispute resolution costs.

These behavioral adaptations are a second reason why the “6:1” ROI cannot be treated as a scalable constant. The more the system stresses a particular enforcement channel, the more taxpayers have incentives to shift behavior toward channels that are harder to police or more efficient from the taxpayer’s perspective (Costlier for the tax collector). At scale, this can reduce the marginal yield of enforcement and can create frictions that affect future taxable activity at the margin.

Even proponents of increased IRS funding recognized the political and practical risks of broad-based enforcement expansion. Secretary Yellen’s 2022 letter emphasized that audit rates should not increase for taxpayers below $400,000 in income, highlighting that enforcement strategy was constrained by legitimacy and feasibility considerations, not merely budget. [10]

Conclusion: a disciplined way to discuss the tax gap

A serious discussion of the Tax Gap should begin with definitions and measurement, not with slogans.

- The Tax Gap measures the difference between estimated true liability and amounts paid. [1]

- The gross Tax Gap is not the collectible number; the IRS already accounts for late and enforced payments and still projects a large Net Tax Gap. [2]

- The largest component, Under Reporting, is also the least directly observable and most dependent on inference and methodological choices. [4]

- International comparisons often fail because they compare different taxes, scopes, and denominators. [5]

- Enforcement can raise revenue, but returns decline as enforcement scales, and CBO explicitly models diminishing ROI. [7]

- Political soundbites such as “$6 for every $1” should be read as claims about limited, high-yield margins, not as a credible strategy to eliminate the entire tax gap. [6][7]

The appropriate framing is not “ignore enforcement,” but neither is it “enforcement will solve it.” The Tax Gap is best treated as a systems problem: strengthen observability where feasible, reduce needless complexity and ambiguity, modernize administrative capacity, and recognize that the last increments of compliance are costly and behaviorally adaptive. Enforcement remains a tool, but it is not a miracle.

References

[1] Internal Revenue Service. 2025. “IRS – The Tax Gap.” https://www.irs.gov/statistics/irs-the-tax-gap

[2] Internal Revenue Service. 2024. “Tax Gap Projections for Tax Year 2022 (Publication 5869).” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5869.pdf

[3] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. 2024. “Tax Gap (Financial Report of the U.S. Government excerpt).” https://fiscal.treasury.gov/files/reports-statements/financial-report/2024/tax-gap.pdf

[4] U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2024. “Tax Gap: IRS Should Take Steps to Ensure Continued Improvement in Its Tax Gap Estimates (GAO-24-106449).” https://www.gao.gov/assets/880/870773.pdf

[5] European Commission, Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union. 2024. “VAT Gap.” https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/taxation/vat/fight-against-vat-fraud/vat-gap_en

[6] Bloomberg. 2013. “IRS Enforcement Spending Yields $6 for Every $1, Lew Says.” https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-05-08/irs-enforcement-spending-yields-6-for-every-1-lew-says

[7] Congressional Budget Office. 2024. “How Changes in Funding for the IRS Affect Revenues.” https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-02/59972-IRS-Rescissions.pdf

[8] U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2024. “U.S. Department of the Treasury, IRS Release New Analysis on the Inflation Reduction Act’s IRS Investments.” https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2079

[9] Internal Revenue Service. 2024. “Return on Investment: Re-Examining Revenue Estimates for IRS Funding (Publication 5901).” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5901.pdf

[10] U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2022. “Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen Sends Letter to IRS Commissioner Rettig.” https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0918

[11] Truthout. 2021. “With Tax Dodgers Costing Us $7 Trillion, Ro Khanna Says “Audit the Ultra-Rich.” https://truthout.org/articles/with-tax-dogers-costing-us-7-trillion-ro-khanna-says-audit-the-ultra-rich