The National Debt (For Non-Economists)

Confused about the National Debt, why you hear so many different numbers, and what they mean. Here’s a plain English explainer to help you make sense of it all. The National Debt is the total amount the U.S. Federal government owes to its creditors. It does NOT include the Debt held by State and Local Governments. Think of the National Debt as the running total of past annual deficits (when the government spends more than it collects in taxes and other income) minus any surpluses (when it collects more than it spends). The debt grows when there’s a deficit and shrinks—at least relatively—when there’s a surplus or when growth/inflation outpace new borrowing. [1][5]

Terms you should know:

- DEFICIT: A deficit is a one-year budget shortfall (this year’s shortfall, which can occur every fiscal year).

- NATIONAL DEBT: The debt is a accumulated total of all Deficits minus any Surpluses (the total outstanding IOUs accumulated over time).

The U.S. Treasury’s Debt to the Penny website publishes the official daily total and its two big parts (explained below). You can look up yesterday’s number, last month’s, or data back to 1993. [2]

“Debt to the Penny is the total debt of the U.S. government and is reported daily.” [2] (See the Treasuries Debt to Penny site HERE)

National Debt

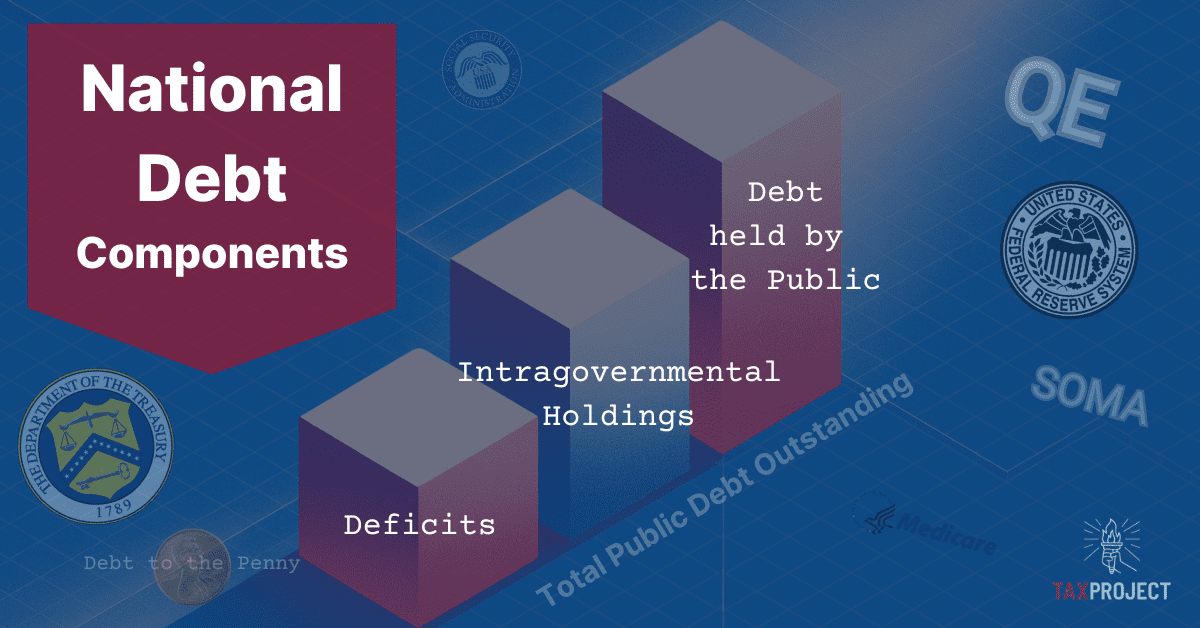

National Debt Components

When people talk about the “National Debt,” they often mean one of three closely related figures:

- Debt held by the public

This is U.S. Treasury securities (Bills, Notes, Bonds, TIPS, etc.) held outside federal government accounts—by households, businesses, pension funds, mutual funds, state and local governments, foreign investors, and the Federal Reserve (America’s central bank). It’s the broadest “market” concept and is the figure economists often use when comparing debt to the size of the economy (debt-to-GDP). [3][4]

Treasury defines it as “all federal debt held by individuals, corporations, state or local governments, Federal Reserve Banks, foreign governments, and other entities outside the United States Government.” [3]

- Intragovernmental holdings

These are Treasuries held within the federal government – mainly trust funds such as Social Security and Medicare. When these programs run surpluses, they invest in special Treasury securities; when they run cash shortfalls, Treasury redeems those securities to pay benefits, and the government borrows from the public if needed. [4][1] - Total Public Debt Outstanding

This is simply the addition of (1) Debt held by the public + (2) Intragovernmental holdings. This is the top-line number on Debt to the Penny. [2][4]

Total Public Debt Outstanding = Debt held by the public + Intragovernmental holdings

Why the distinctions matter:

- Debt held by the public is what markets price and what drives interest costs the government pays to outside holders (including the Federal Reserve).

- Intragovernmental debt reflects promises among parts of the federal government; it affects future cash needs but doesn’t have the same market dynamics.

- Total Public Debt Outstanding is the full legal amount subject to the debt limit (with a few technical exclusions), which matters for statutory debt-limit debates. [4][5] When there are discussion in Congress about the Debt ceiling this is the number discussed.

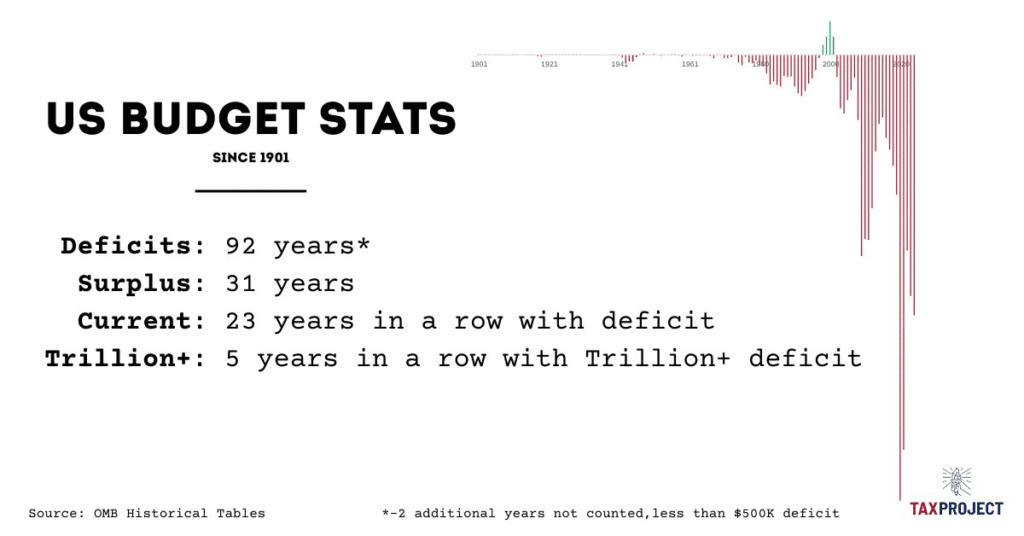

How deficits add to the National Debt

Each fiscal year, Congress sets taxes and spending. If outlays (spending) exceed receipts (revenue), the government runs a deficit and must borrow by issuing new Treasury securities. Those new securities add to Debt held by the public, and thus to the total debt. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) publishes baselines and explains the arithmetic and risks of rising Net interest (what the government pays in interest). In 2024, Net Interest on the Debt alone was over $1 Trillion, making it the 3rd largest budget item, larger than National Defense. [5][7][18][22]

In years with a surplus, Treasury can redeem (pay down) outstanding securities or reduce the need to issue new ones—slowing debt growth. But because recent years have seen persistent deficits, the debt has generally climbed. [22]

“Debt to the Penny”

For the Official US National Debt numbers, you can go straight to Treasury’s Debt to the Penny page. On the site you can:

- See today’s total (updated daily except during weekends and holidays) and the split between debt held by the public and intragovernmental holdings.

- Download historical CSVs to chart the series yourself.

- Check big shifts around tax dates, debt-limit suspensions, or major fiscal packages. [2][15]

Pair that with Treasury’s Public Debt Reports for monthly statements and context. [4] (Treasury Public Debt Reports Here)

Who does what: Role of Treasury vs. the Federal Reserve

The U.S. Treasury (through the Bureau of the Fiscal Service and the Office of Debt Management) issues Treasury bills, notes, and bonds to finance the government at the lowest cost over time. It auctions securities on a regular calendar and redeems them at maturity. Treasury also manages cash (the Treasury General Account at the Fed) to pay the government’s bills. [4][2]

The Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) is the central bank. It does not set taxes or spending and does not decide how much debt the government issues. The Fed’s role here is monetary policy: it influences interest rates and financial conditions. The Fed has a dual mandate to maintain stable prices (control inflation), and manage Employment (manage environment to keep unemployment low). It buys and sells Treasuries only in the secondary market (from dealers), not directly from the Treasury, to maintain its independence and implement policy. [6]

“The Fed does not purchase new Treasury securities directly from the U.S. Treasury, and purchases…from the public are not a means of financing the federal deficit.” [6]

The New York Fed executes these operations for the System Open Market Account (SOMA), the consolidated portfolio of Treasuries and other securities the Fed holds. [12]

What is Quantitative Easing (QE)?

Quantitative easing (QE) is a policy the Fed uses in severe downturns or when short-term interest rates are already near zero. When the Fed is using QE, the Fed buys longer-term securities, such as Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities, to push down longer-term interest rates and support the economy. The Fed conducted several large purchase programs after the 2008 Financial Crisis and again during 2020-21 COVID Pandemic. [8][21][14]

Mechanically, when the Fed buys a Treasury, it pays by crediting banks’ reserve accounts at the Fed. That swaps a Treasury security held by the public for a bank reserve (a deposit at the Fed). Crucially, this transaction does not change the total amount of Treasury debt outstanding—it changes who holds it (more at the Fed, less in private hands). [10][6]

“When the Federal Reserve adds reserves…by buying Treasury securities…This process converts Treasury securities held by the public into reserves…[and] does not affect the amount of outstanding Treasury debt.” [10]

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet

Does QE “add to the National Debt”?

No. QE doesn’t authorize or cause Treasury to borrow more or add to the Debt. The deficit determines how much debt Treasury must issue. QE affects yields and liquidity by changing the composition of holders (more at the Fed/SOMA, fewer in private portfolios), not the quantity of debt the government has issued. The Fed repeatedly emphasizes it does not buy securities directly from Treasury or to finance deficits. [6][7][9] (Federal Reserve)

QE can, however, indirectly affect the budget over time through interest rates (lower yields can reduce Treasury’s borrowing costs; the reverse is true when QT—quantitative tightening—lets the portfolio roll off and rates are higher). Several primers walk through these channels. [17][18][7]

How interest flows work when the Fed holds Treasuries

Here’s the accounting workflow in plain English:

- Treasury pays interest on all outstanding Treasuries—whether they’re held by a pension fund, a foreign central bank, or the Federal Reserve. That shows up in the budget as Net interest outlays (spending). [18]

- When the Fed holds Treasuries (in SOMA), the interest it receives becomes part of the Fed’s net income.

- After covering its expenses, the Fed historically remits (gives back) its profits to the Treasury (these are “remittances”). In years when those profits are large, Treasury effectively gets back a chunk of the interest it paid—reducing the government’s overall cost ex post (after the fact). [9][20]

- In times (like 2023-25) when the Fed’s interest expenses (mainly interest it pays banks on reserve balances and reverse repos) are greater than its interest income the Fed stops remitting, records a “deferred asset” (an IOU to itself), and resumes remittances only after it returns to positive net income. That deferred asset does not require taxpayer funding; it’s paid down by future Fed profits before any cash flows back to Treasury. [1][5]

“When the Fed’s income exceeds its costs, it sends the excess earnings to the Treasury…When its costs exceed its income, it creates a ‘deferred asset’…and resumes sending remittances after that is paid down.” [1]

Bottom line: whether private investors or the Fed hold a given Treasury, Treasury’s legal obligation to pay interest is the same. The difference is that Fed-held interest often returns back to Treasury (when Fed profits are positive), lowering the government’s ultimate net cost over time. [9][20]

Review of National Debt Concepts

- Debt grows because of deficits. Congress’s tax and spending choices determine if there will be an annual deficit or surplus; deficits add to debt. Surpluses reduce the debt. [5][22]

- Debt has two big parts. Debt held by the public (including the Fed) plus intragovernmental holdings (trust funds) equals Total Public Debt Outstanding. [2][4] (Fiscal Data)

- QE doesn’t “create” more Treasury debt. It changes who holds it and influences rates and liquidity; the Fed buys in the secondary market and does not finance deficits. [6][10][7]

- Interest flows are circular when the Fed holds Treasuries. Treasury pays interest; the Fed usually remits (returns) net income back to Treasury; during periods of negative net income, remittances pause and a deferred asset records what will be repaid from future profits. [1][5][20]

- You can verify every number daily on Treasury’s Debt to the Penny site, and pair it with monthly public debt reports for detail. [2][4]

FAQ and Common Misconceptions

“If the Fed buys Treasuries, isn’t that just ‘printing money’ to fund the government?”

No. The Fed buys from dealers in the open market, not from Treasury. Fed purchases swap Treasuries for bank reserves; they don’t change the amount of debt or directly finance the deficit. [6][10][7]

“Doesn’t the debt count everything the government owes, including future Social Security benefits?”

The debt is legal obligations already issued (Treasury securities). Future promises (like future benefits) affect the budget and future borrowing, but they aren’t counted as debt until the government issues securities to pay for them. These are called Unfunded Liabilities (See our Article). Check the Debt to the Penny site for what is counted. [2][4][5]

“Why do some charts focus only on debt held by the public?”

Because that’s the portion traded in markets, driving interest costs and macro impacts. It’s also the number most used in economic comparisons (for example, debt-to-GDP). [5]

Debt Guru: How to read the daily debt like a pro

- Visit Debt to the Penny site and note Total Public Debt Outstanding.

- Compare the split between public and intragovernmental. Persistent deficits typically raise the public share over time.

- If rates are rising (or have risen), expect net interest in the budget to climb; CBO’s primers explain why interest costs can grow faster than the economy when debt is large. [2][18][22]

If you want more depth on how the Fed runs these operations, the New York Fed’s archive on large-scale asset purchases and the Board’s description of the System Open Market Account are the canonical sources. [8][12]

Putting it all into Context

If you want to understand how big the National Debt is, how it relates to other things like the size of our economy, how the budget deficits and surpluses compare in charts over the years historically and how that impacts the debt in charts, check out that and more in the Tax Project Institute’s Smarter Citizen App (A Free Citizen App, just register – no credit card and you’re in!)

Glossary

- Treasury security: An IOU the U.S. government sells to borrow money (Bills mature in a year or less; Notes in 2–10 years; Bonds in 20–30 years; TIPS are inflation-protected). Holders earn interest and get their principal back at maturity. [3]

- Debt held by the public: Treasury IOUs owned by investors outside the federal government, including the Federal Reserve. [3]

- Intragovernmental holdings: Treasury IOUs held by government accounts (e.g., Social Security trust funds). [4]

- QE (quantitative easing): The Fed’s large purchases of longer-term securities to lower long-term interest rates when the economy needs help and short-term rates are generally already lower. [21][8]

- Remittances: Fed profits (if any) sent to Treasury after covering expenses; paused when the Fed’s interest expenses exceed income (recorded as a “deferred asset”). [5][1]

References

[1] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2024, July 19). How does the Federal Reserve’s buying and selling of securities relate to the borrowing decisions of the federal government? https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[2] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Data. (n.d.). Debt to the Penny (daily dataset; coverage back to 1993). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/ (Fiscal Data)

[3] U.S. Department of the Treasury. (n.d.). Public Debt FAQs (definitions of debt held by the public & intragovernmental holdings). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://treasurydirect.gov/ (TreasuryDirect)

[4] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Data. (n.d.). Monthly Statement of the Public Debt (MSPD) (monthly dataset). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/ (Fiscal Data)

[5] Congressional Budget Office. (2020, March 12). Federal Debt: A Primer. https://www.cbo.gov/ (Congressional Budget Office)

[6] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, January 17). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035. https://www.cbo.gov/ (Congressional Budget Office)

[7] Congressional Budget Office. (2025, March 27). The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055. https://www.cbo.gov/ (Congressional Budget Office)

[8] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2025, September 23). Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB): FAQs (includes note that asset purchases convert Treasuries to reserves without changing outstanding Treasury debt). https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[9] Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (n.d.). Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs): Program Archive. Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://www.newyorkfed.org/ (Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

[10] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2016, August 25). Is the Federal Reserve “printing money” in order to buy Treasury securities? https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[11] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2025, June 13). About the Fed — Chapter 4: System Open Market Account (SOMA). https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[12] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (n.d.). Fed Balance Sheet—Table 1 (popup): U.S. Treasury, General Account (definition of the Treasury General Account). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[13] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (n.d.). H.4.1—Factors Affecting Reserve Balances (current and archived releases). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[14] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED Blog). (2023, November 20). Federal Reserve remittances to the U.S. Treasury. https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/ (FRED Blog)

[15] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (via FRED). (n.d.). Liabilities & Capital: Earnings Remittances Due to the U.S. Treasury (RESPPLLOPNWW) (weekly series). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RESPPLLOPNWW (FRED)

[16] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2024, March 26). Federal Reserve Board releases annual audited financial statements (deferred-asset explanation). https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[17] Anderson, A., Ihrig, J., Kiley, M., & Ochoa, M. (2022, July 15). An Analysis of the Interest Rate Risk of the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet (Part 2). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes. https://www.federalreserve.gov/ (Federal Reserve)

[18] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. (n.d.). Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS) (receipts, outlays, surplus/deficit; means of financing). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fiscal.treasury.gov/reports-statements/mts/ (Bureau of the Fiscal Service)

[19] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Data. (n.d.). America’s Finance Guide: National Debt (dataset links and coverage notes—e.g., Debt to the Penny since 1993). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/ (Fiscal Data)

[20] Data.gov (U.S. General Services Administration). (n.d.). Debt to the Penny (dataset catalog entry and composition note). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://catalog.data.gov/ (Data.gov)

[21] Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (2022, February 11). FAQs: Treasury Purchases (secondary-market operations). https://www.newyorkfed.org/ (Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

[22] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Data. (n.d.). Historical Debt Outstanding (long-run series). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/ (Fiscal Data)